The Art of Eating the Frog

How one distracted monk found his voice—one croak at a time

Brother Imbas lived in the Abbey of the Narrow Way, just beyond the mist-wrapped Bog of Allen, where prayers rose like peat smoke and boots squelched more than they echoed. The abbey was known for its rigor—a place of bells, strict hours, silent meals, and no-nonsense schedules.

Imbas had chosen it willingly.

He had what the abbot once called “a lively mind.” Which was monastic code for: he couldn’t finish one task without chasing five others. In the time it took another monk to sweep a corridor, Imbas had alphabetized the cleaning supplies, drafted a composting plan, written a sonnet about dust, forgotten it halfway through, and redesigned the monastery’s entire broom storage system.

He thought the abbey’s rigid rhythm would tame his mind. But the bells, rather than anchoring him, often tolled at the precise moment he found focus—yanking him out like a fish on a hook. And during silent prayers, while his brethren sat like still pools, Imbas’ mind rippled and churned—plots, verses, recipes, inventions.

“You need discipline,” the abbot said. “Your mind is like a frog. Always hopping.”

“Should I… catch it?”

“No. Calm it. Like a pond.”

Then the old man’s eyes gleamed.

“You’ll sing the Exultet this Easter.”

Imbas froze. The Exultet. The holiest, longest, most solemn chant of the liturgical year. Sung alone. In darkness.

“But—” Imbas began.

“No but,” said the abbot. “There’s that frog again. Get it under control. Start practicing.”

The Plan

Imbas stared at the scroll of notes as if it might start singing on its own.

The abbot didn’t know: it wasn’t just his mind that hopped like a frog. His voice sounded like one too. It cracked. It warbled. It sometimes forgot which syllable came next and wandered off entirely.

So Imbas did what many distracted minds do best.

He made a plan.

A long, color-coded, overly ambitious plan. With sub-tasks. Backup options for every vocal disaster.

Then he reorganized the sacristy.

Then he labeled the candles by burn time.

Then he rewrote the monastic rules of St. Columbanus with improved punctuation.

“No time left to practice today,” he said cheerfully. “But tomorrow. Definitely tomorrow.”

And tomorrow croaked past.

So he sought help.

The Nun and the Druid

The nun from the nearby abbey had a voice like morning light—clear, gentle, impossible to imitate. She tried to teach him. She was kind. Patient.

It only made Imbas feel worse.

He couldn’t match her grace. Couldn’t even stay on pitch. Soon, he began making excuses to skip practice. Headache. Laundry. A calling elsewhere.

The sister, not fooled, sent her uncle.

A druid.

He appeared barefoot in the cloister after morning prayer, cradling a very moist, very smug-looking frog.

“I heard you’re struggling with your singing,” said the druid, eyes twinkling.

Imbas blinked. “Is… that for me?”

“It’s your teacher.”

The frog blinked, too.

“I want you to boil it,” said the druid, offering it forward. “And eat it. Tomorrow morning.”

Imbas recoiled. “Is this some old pagan ritual?”

“No. Just good advice.”

He leaned in.

“Eat the frog first. Everything after that gets easier.”

The Patience of the Frog

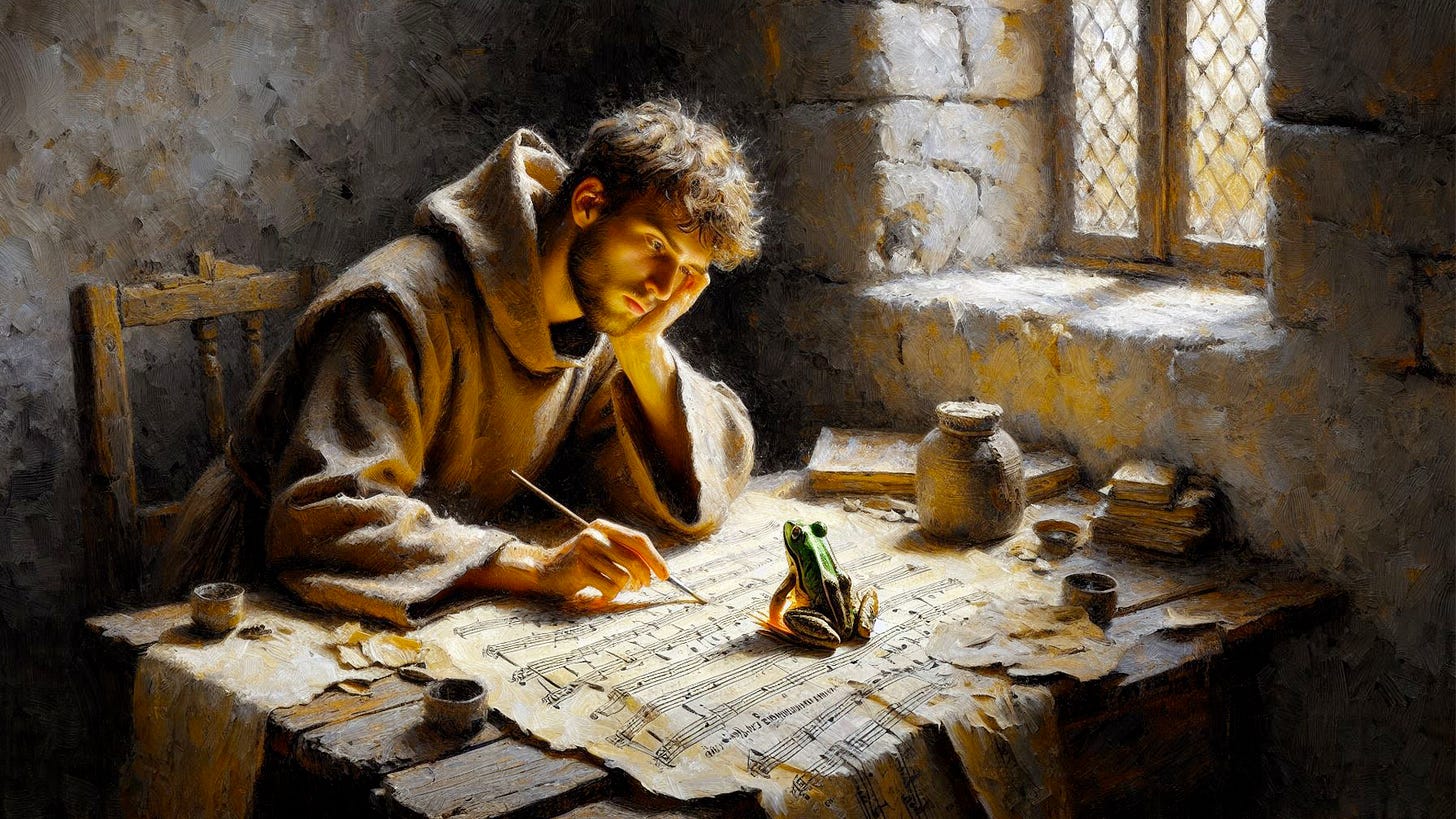

The next morning, the frog sat on Imbas’ desk. Warty. Silent. Unbothered.

“I’m not eating you,” the monk said. “You smell of pondweed and bad decisions.”

The frog stared.

Imbas lit a candle. Unrolled the parchment.

Sang the first word.

It cracked like dry kindling.

But it didn’t break him.

The frog croaked once. As if in approval.

So he sang another.

The frog blinked. Hopped off the table.

Imbas chased it—briefly. Got distracted. Reorganized the ink pots instead.

That night, slumped on his cot, he stared at the ceiling and scolded himself.

“I’m lazy. Undisciplined. Everyone else manages. I can’t even sing one chant without falling apart.”

He turned over, pulled the blanket over his head, and whispered to the dark, “Why can’t I just try harder?”

In the silence, a soft croak came from the other side of the room.

Not judgment.

Not disappointment.

Just a frog, sitting still. Waiting.

Progress

The next morning, the frog was back on his desk—quiet as ever.

So was the scroll.

So was the candle.

He sang one note.

Then two.

He hummed while kneading bread, letting the dough stretch the syllables for him.

He whispered the chant into the old stone well and listened to the echo answer with faint corrections.

He recited psalms to the abbey cat.

He practiced by reading the soup menu aloud in a rich baritone.

And always—he stopped when it got too hard.

But he always started again.

The frog never blinked in disappointment. Never croaked in critique.

It simply stayed.

The chant came. Slowly. Unevenly. But it came.

The Vigil

The Easter Vigil arrived.

The chapel was full of shadow and waiting. Incense clung to the arches like breath in cold air.

The abbot handed him the scroll. And the candle.

Imbas stepped forward.

Heart thudding. Hands shaking.

He opened his mouth.

And sang.

His voice wavered. Once. Twice.

But it didn’t falter.

The chant rose, flickering and fragile, threading through the dark like a single flame trying to remember how to burn.

The novices held their breath.

By the baptismal font, the frog croaked once.

Perfectly in pitch.

The Boiling Point

When spring warmed the pond, the druid returned, humming a tune older than any scroll.

He found Imbas by the water’s edge, singing quietly to a very familiar frog.

“You never cooked him,” said the druid.

“No,” said Imbas. “But he still helped.”

“Learned the recipe after all?”

Imbas shook his head. “I never figured out how to cook a frog. Wouldn’t he just jump out the moment the water boiled?”

The druid chuckled. “Aye. But not if you warm it slowly. Bit by bit. He won’t even notice.”

He gave Imbas a knowing look.

“That’s what you did, isn’t it? Started small. Let yourself warm up.”

He opened his hands. The frog hopped in, like it had done this before.

“There are others who need help too.”

And with that, the druid wandered off—humming something suspiciously close to the Salve Regina.

The Novice

Years later, Abbot Imbas led the Abbey of the Winding Way—a place where detours were expected, and patience was a spiritual practice.

One afternoon in the garden, a novice approached, tears brimming, a scroll clutched tight.

“I can’t do it,” the boy said. “You asked me to sing at Easter, but I can’t focus. I panic. And this strange old man gave me this frog and told me to eat it first. But I can’t!”

Imbas chuckled. “Then don’t.”

“Don’t?”

“For some people, starting with the hardest thing works. They leap. But others—most of us—have to warm the water first.”

He crouched beside the boy, voice low.

“I used to think I was lazy. Broken. That if I just tried harder, I’d succeed. But trying harder isn’t the same as starting small.”

He glanced toward the pond. The frog blinked slowly from its lily pad.

“I judged myself so harshly. Every failure felt like a verdict. But the frog? The frog never judged me. He just sat there. Waiting. So I did too.”

He placed a hand on the boy’s shoulder.

“I won’t judge you either.”

The boy sniffed. “I think I can sing one note.”

“Perfect,” said Imbas. “Tomorrow—try two.”

From the pond, the frog croaked.

Still perfectly in pitch.

Probably smug about it, too.

This is such a great story. I think I needed to hear it. Thank you

Odd how that Old Druid always shows up.